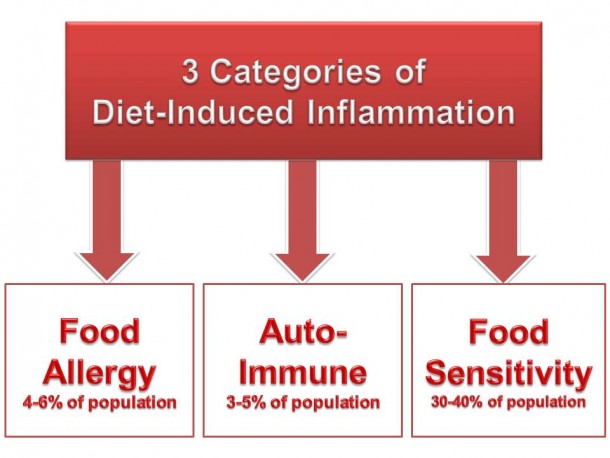

Food and food-chemical sensitivities are a highly complex category of non-allergic (non-IgE), non-celiac inflammatory reactions. They involve multiple mechanisms and may be governed by either innate or adaptive immune pathways. They’re one of the most important sources of inflammation and symptoms across a wide range of chronic inflammatory conditions. They are also one of the most clinically challenging.

Due to their inherent clinical and immunologic complexities, as well as a lack of general knowledge within conventional medicine of their role as a source of inflammation in IBS, migraine, fibromyalgia, arthritis, GERD, obesity, metabolic syndrome, ADD/ADHD, autism, etc., food and food-chemical sensitivities remain one of the most under-addressed areas of conventional medicine.

Clinical Complexities

Food and food-chemical sensitivities have clinical characteristics that make it very challenging to identify trigger foods. For example, symptom manifestation may be delayed by many hours after ingestion; reactions may be dose-dependent; because of a breakdown of oral tolerance mechanisms, there are often many reactive foods and food chemicals; even so-called anti-inflammatory foods, such as salmon, parsley, turmeric, ginger, blueberry, and any “healthy” food can be reactive.

Medical Conditions Where Sensitivities Can Play a Primary or Secondary Role

Gastrointestinal

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Functional Diarrhea

GERD

Crohn’s Disease

Ulcerative Colitis

Microscopic Colitis

Lymphocytic Colitis

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

Endocrine

Obesity

Neurological

Migraine

ADD/ADHD

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Epilepsy

Depression

Insomnia

Restless Leg Syndrome

Urological

Interstitial Cystitis

Gynecological

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Musculoskeletal

Fibromyalgia

Inflammatory Arthritis

Dermatological

Atopic Dermatitis

Urticaria

Psoriasis

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Immunologic Complexities

Recent research into adverse reactions to gluten has uncovered a new form of diet-induced inflammation termed “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” (GS). Gluten sensitivity is 6-8 times more prevalent than celiac disease, can provoke a wide range of clinical symptoms, and has been proven to activate the innate immune system, a branch of the immune system that has been almost completely neglected for years by researchers as a source of diet-induced inflammation and symptoms. But gluten is just one potential piece of the puzzle. As stated previously, any food can trigger an inflammatory response, even so-called anti-inflammatory foods. The key is to know which specific foods and food chemicals are triggering reactions in each specific patient. That’s the beginning of the best way to design an eating plan that will produce the maximum clinical benefit.

Common feature of Diet-induced Inflammation

The single common feature of all diet-induced inflammatory reactions is that they ultimately cause mediator release (cytokines, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, etc.) from various white blood cells (neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, lymphocytes). This is true whether reactions are immediate or delayed, whether dose-dependent or not, whether governed by the innate or adaptive immune systems, whether cell-mediated or humoral-mediated, and whether inflammation remains at a sub-clinical level or becomes clinically symptom-provoking. All food-induced inflammatory reactions involve mediator release, which is the single most important event leading to all the negative effects your patients suffer, including symptom generation.